Petrikron

BEING A RECORD OF THE

ALEATORY INVESTIGATIONS

OF THE DEVIL IN THE HOROLOGE

stone clock

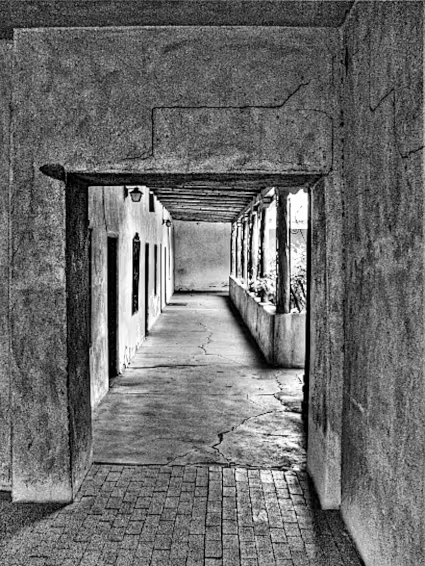

Like its namesake—a bricolage clock that didn’t tell time—this site is a space for play. Composed of ruminations, fragments of ideas, photographs, records of encounters with people, some living some dead some neither one nor the other, it has only the form imposed on it by its medium. I may structure it using the meandering course of my reading or not. It’s a plastic ateleological machine.

Shadows, saints, and roadkill

and a pen for seeing

and the hands that sing a Lakota blessing

and the cracked glaze calligraphy of an old bowl

and a fractured conversation between insentients

and a couple of hats

image abused without permission

Autumn shades

It’s hard to take a photograph around here without a saint in it. They are never without a shadow, not necessarily their own, that appears to be casting the saint.

The effect is most noticeable in the fall: the halcyon days of any shadow, when instead of being cast by the light, a shadow casts the light through the prism of the object.

The object becomes a conduit rather than a barrier and everything changes.

Two pair

Reading on a park bench elbows on knees, a strip of sidewalk is framed by the top of a book and the brim of a hat. Through this strip pass two pair of shoes. One pair says to the other, “You should have seen the roadkill I saw today.”

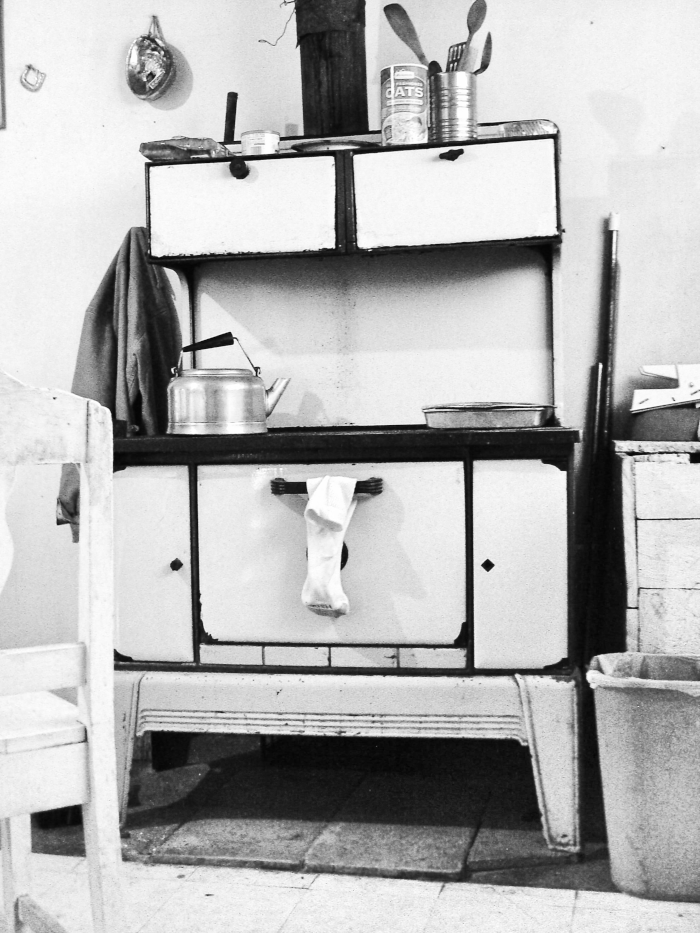

Charcoals

Two portraits done by an itinerant artist, when they were two failed harvests from being itinerant themselves.

Breaking

You can tell how much whiskey to pour someone by observing how they break. Breaking is handing the empty glass off to the hand that will put it down. If a person breaks to the left, you fill their glass two-thirds full. If they break to the right, you fill their glass [I missed what was said in the dream here] If they break with both hands, you throw the whiskey in the oven followed by a lit match and enjoy the explosion.

“Demolitions: I stretch out full length atop my triturations, I inhabit my demolitions.”

The Monkey Grammarian

Octavio Paz

The Borderline’s Battle

of who could care less

It allows them to feel righteous and alive without the bother of being either.

Empty refrigerators

They rattle and hum; their insides are barren and cold; their exteriors collect magnetized slogans.

They live the examined life and have the selfies to prove it. They don’t reason, they emote. They don’t draw conclusions from inferences; they accrete impressions from whatever purveyor or puppetmaster. They call their freedom from reason independent thinking. “I want to hear it from the horse’s mouth,” they’ll say, as they stick their head in the nearest box to hear it not from the horse’s mouth but from the horse’s trainer who, by extension, is their trainer.

Guy Debord’s thesis 218 says it best:

Imprisoned in a flattened universe bounded by the screen of the spectacle, behind which his own life has been exiled, the spectator’s consciousness no longer knows anyone but the fictitious interlocutors who subject him to a one-way monologue about their commodities and the politics of their commodities. The spectacle, in its entirety, is his “mirror sign,” presenting illusory escapes from a universal autism.

The Society of the Spectacle

transl. Ken Knabb

SCRIPTIOCONTINUA

A lexical rapprochement heard by the reading eye.

Antinomial

where it lies

there it is not

sad loss when you find it

sweet the bitter resin on your tongue

fierce the wind that blows cold

Afterword

“Before you read any further, let me tell you why that would be a bad idea.”

Martin Hilpert

From his not-to-be-missed note to the reader in

Construction Grammar and its Application to English

Edinburgh University Press Ltd, 2014

ISBN 978 0 7486 7588 3

Family

I’m waiting at a bus stop in Albuquerque. A Native American with a backpack approaches me for some change to help him out. I have a dollar in my pocket left over from bus fare and give it to him. He thanks me and says he can get himself a drink now. I said,“You’re kidding me. If I thought you were going to spend it on booze, I would have put it towards a beer for myself.” He laughed, embraced me, and called me a brother. We talked.

We talked like brothers waiting at a bus stop do, and during our conversation he performed a song—a blessing, it turned out, in Lakota. He spoke a number of native languages: Lakota and Diné and the rest he listed by speaking a monostich of each. At one point in the song, it looked like he crossed himself.

We talked more, and he performed the song again. This time I noticed that he made a gesture of touching the ground before the crossing. I asked about it: the touching of the ground was for Mother Earth, the crossing was for The Heavenly Father, and the blessing was for his brother who was leaving on a bus.

The site’s author can be reached at words at this domain.